Identifying wine aromas can be overwhelming for someone just beginning their wine journey. Even when using an aroma wheel or wine lexicon from the Wine and Spirit Education Trust (WSET), there’s always a question about whether someone can genuinely smell a particular characteristic. Or whether they smell a familiar note because it’s something they just read.

To add to the confusion, only some wines exhibit the three main types of wine aromas: primary, secondary and tertiary. The ambiguity makes it difficult for everyone, including wine professionals, to differentiate what they’re smelling and where it derives.

Fortunately, we can help ease confusion surrounding primary, secondary, and tertiary wine aromas by knowing three general steps in winemaking.

Primary Wine Aromas

Aromas that come from the grape and alcoholic fermentation are primary wine aromas. Without these two things, wine would not exist. Therefore, every wine exhibits at least one or two, often several, primary characteristics.

To identify primary wine aromas, remember that grapes are fruit. Therefore, most primary notes will be fruity. Various citrus, tree, stone, or tropical fruit aromas are typical for white wine. For red wine, it’s usually easy to differentiate red fruit or berry aromas, like raspberry or red currant, from black or darker fruits, like black cherry or plum.

Some primary aromas can be herbaceous since grapes grow on a vine plant. A well-known example is the green bell pepper, or capsicum, characteristic of Cabernet Sauvignon or Cabernet Franc. Herbal attributes include anything from eucalyptus and mint to fennel or dill. Floral is also a popular primary category, including rose, violet, blossom, or honeysuckle.

Lastly, the vine grows from the earth, meaning drinkers may even pick up on earth-like qualities like stone or mineral – depending on the soil type.

Secondary Wine Aromas

The next step of winemaking, post-fermentation, is where secondary wine aromas come to be. This stage sees human intervention. So, while tasting, if an aroma reveals itself that can’t be found in nature, it’s likely a secondary characteristic.

Hints of biscuit, bread or dough — as seen in Champagne — often indicate a period of lees aging (when wine remains in contact with dead yeast cells). Buttery or creamy notes come from malolactic fermentation, a second fermentation that converts tart-tasting malic acid to softer-tasting lactic acid.

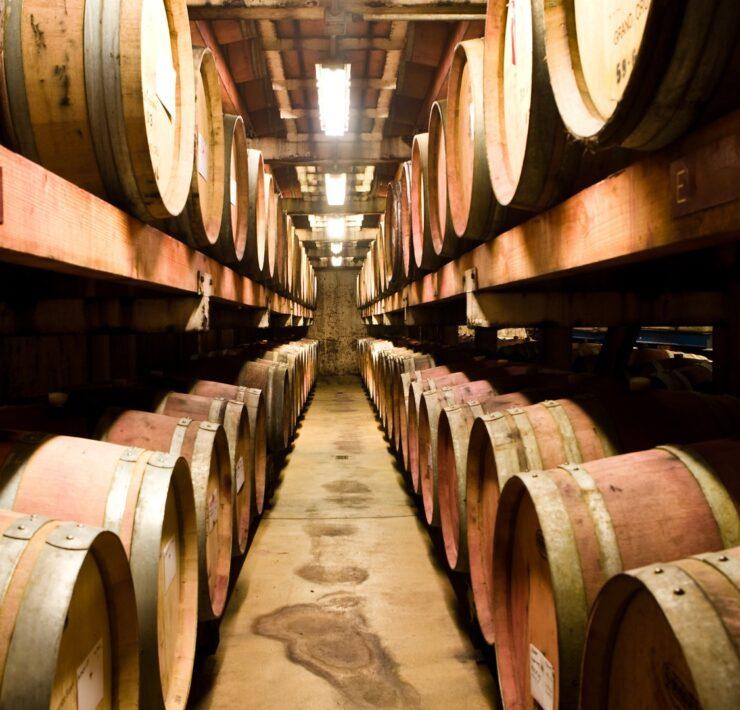

Oak aging offers the most diversity when it comes to secondary aromas. The type of oak and the length of time the wine spends in a barrel can dictate whether vanilla, toast or smoke aromas are wafts, hints, or intensely full-on.

Wines without intervention that are made without additional fermentation or oak aging will often only display primary aromas. This includes youthful wines meant to be drunk within their first year and usually fermented in stainless steel or concrete eggs.

Tertiary Aromas

Tertiary wine aromas are undoubtedly where the most confusion lies. These characteristics come about by way of wine maturation. Because most wines for sale are for immediate consumption, few drinkers get to experience tertiary qualities.

An extended period of bottle aging is where tertiary notes are born. For example, fruit development in white wine sees a transition from fresh to dried. Red wine is similar and can also exude cooked/stewed fruit or jam-like qualities.

Over time, new notes can also appear. For example, warm spices, nuts and hints of honey can develop in white wines, while red wine often sees earthy evolution with forest floor and vegetal qualities or the smell of a classic barnyard.